by katie | May 30, 2018 | Blog, Weave Blog

Once you have decided on a project you may want to work out how much yarn you are going to need. This may be so you can buy or dye the correct amount without vastly over or under estimating.

The following will take you through the calculation to do this. It looks like a lot but they should be relatively straight forward things to work out. For the sake of simplicity I will work in centimetres/meters but the same can be applied to inches/yards.

The calculaion is as follows:

Total number of ends x total length of warp (m) = amount of yarn needed (m)

How to work out the total number of ends

- EPC (see calculating sett) x (width of woven piece (cm) + shrinkage/take-up (cm)) = Total number of ends

- The shrinkage/take-up is usually assumed to be 10% of the width of the woven piece but this can vary by a large amount depending on the yarn, structure and finishing. Sampling will give you a more accurate number.

How to work out the total length of the warp

- Length of woven piece(s) (m)+ shrinkage/take-up (m) + yarn wastage (m) = Total length of warp (m)

- If weaving more than one piece add the lengths together

- The shrinkage/take-up is usually assumed to be 10% of the length of the woven piece but this can vary by a large amount depending on the yarn, structure and finishing. Sampling will give you a more accurate number.

- Yarn wastage is the amount of yarn used to tie on to the front beam plus the warp woven for even end distribution plus the loom waste (the amount of yarn left on the loom not able to be woven).

- It is often easier to work out the calculations in cm and then convert to m by dividing by 100 at the end.

As a working example:

Total number of ends:

- 8 EPC

- 50cm wide warp

- 10% of 50cm = 5cm shrinkage/take-up

8 x (50 + 5) = 440 ends

Total length of warp:

- Three 50cm woven pieces = 150cm

- 10% of 150 = 15cm shinkage/take-up

- 10cm to tie on

- 5cm to weave distributing picks

- 50cm left on the loom that cant be woven

150 + 15 + 10 + 5 + 50 = 228cm (2.28m)

440 x 2.28 = 1003.2m of yarn needed for the warp

Calculating the sett

by katie | Apr 26, 2018 | Blog, Weave Blog

What is a sett?

Once you have chosen a yarn(s) to use use for a warp you need to consider the sett. In other words, the number of warp ends you will want to have in your woven cloth per centimetre/inch (ends per centimetre (EPC) or ends per inch (EPI)).

Things that may affect the sett

There are a number of factors that need to be taken in to consideration and may affect the sett you choose:

Weave structure

A weave structure with fewer weft intersections with the warp will require a higher sett. For example a 3/1 twill will require a higher sett than a plain weave.

Final use/aesthetics of the fabric

If the final outcome is to be a lightweight scarf then the sett may need to reduced considerably. On the other hand if the fabric is to be cut and sewn a much higher sett is needed so it holds together well. A higher sett will also make it harder wearing.

Personal preference

Some weavers prefer to use a slightly higher/lower EPC/EPI and may also beat down their weft harder/more softly.

Bearing this in mind the below is only a guide and other factors will affect the sett.

How to work out the sett

To work this out you need to take your yarn and wrap it around a ruler. Do this with no gaps between but ensure the yarn does not bunch up or overlap. Wrap it around in a 1 cm or 1″ section as shown below.

Dividing the number of times the yarn was wrapped by 2 gives you the EPC/EPI of your woven cloth.

This method is usually a good indicator of the number of ends you will need for a balanced plain weave structure. When we talk about a balanced plain weave we mean a plain weave where the warp and weft are equally visible, neither one dominates the other.

For a balanced twill you would use 2/3 of the number of ends round the ruler.

In the photo above the yarn was wrapped around the ruler 14 times within 1cm. This means I would want to start with 7 EPC for a plain weave or 10 EPC for a twill.

If different structures are to be woven then the EPC/EPI will need to be adjusted. There is a formula to work this out mathematically which can be confusing. It may also be affected by previously mentioned variables which cannot be taken into consideration with a formula. The formula is as follows:

S= T X R

bn(I + R)

S is the sett.

T is the number of times the yarn was wrapped around a ruler.

R is how many ends there are in one repeat.

I is the number of weft intersections in one repeat.

I personally prefer to use the first method mentioned and adjust it taking all other aspects of the woven piece in to consideration. Sampling really is the only way to get just the right sett.

by katie | Apr 8, 2018 | Blog, Weave Blog

Yarn is made from a variety of different fibres and it is important to have an understanding of where these fibres come from. The following table show some of the most common types and their origin:

| Fibre type |

Yarn |

Origin |

|

Natural (cellulose)

|

Cotton |

White boll which surrounds the seed of the cotton plant |

| Flax/linen |

Filament fibre from flax plants |

| Hemp |

Hemp plant (a Angiosperm phylum) |

| Jute |

Corchorus olitorius plant |

| Ramie |

Bark of Boehmeria nivea |

| Sisal |

Leaf of the Agave sisalana plant |

| Bamboo |

Stem of the bamboo plant |

| Paper |

Wood pulp |

| Abaca |

Leaf of the banana plant |

| Banana |

Stem of the banana plant |

| Pineapple |

Leaf of pineapple plant |

| Coir |

Husk of the coconut fruit |

| Lyocel (tencel) |

Wood pulp |

| Seacell |

Wood pulp and seaweed (algae) |

|

Natural (protein)

|

Sheep wool |

Sheep hair |

| Alpaca |

Alpaca hair |

| Cashmere |

Cashmere goat |

| Mohair |

Angora goat |

| Angora rabbit |

Angora rabbit |

| Camel |

Camel hair |

| Horse |

Horse hair |

| Lama |

Lama hair |

| Mulberry Silk |

Silkworm cocoons |

| Tussah silk |

Tussah silk moth cocoon |

|

Synthetic

|

Vicsose |

Wood pulp |

| Rayon |

Cellulose from a variety of plants |

| Polyester |

Synthetic resin |

| Elastane |

Minimum of 85% polyurethane polymer |

| Acrylic |

Minimum of 85% acrylonitrile monomer |

Some fibres come from a natural source but are classed as synthetic. This is due to the manufacturing process the fibre has gone through to and whether the end fibre is biodegradable.

by katie | Mar 31, 2018 | Blog, Weave Blog

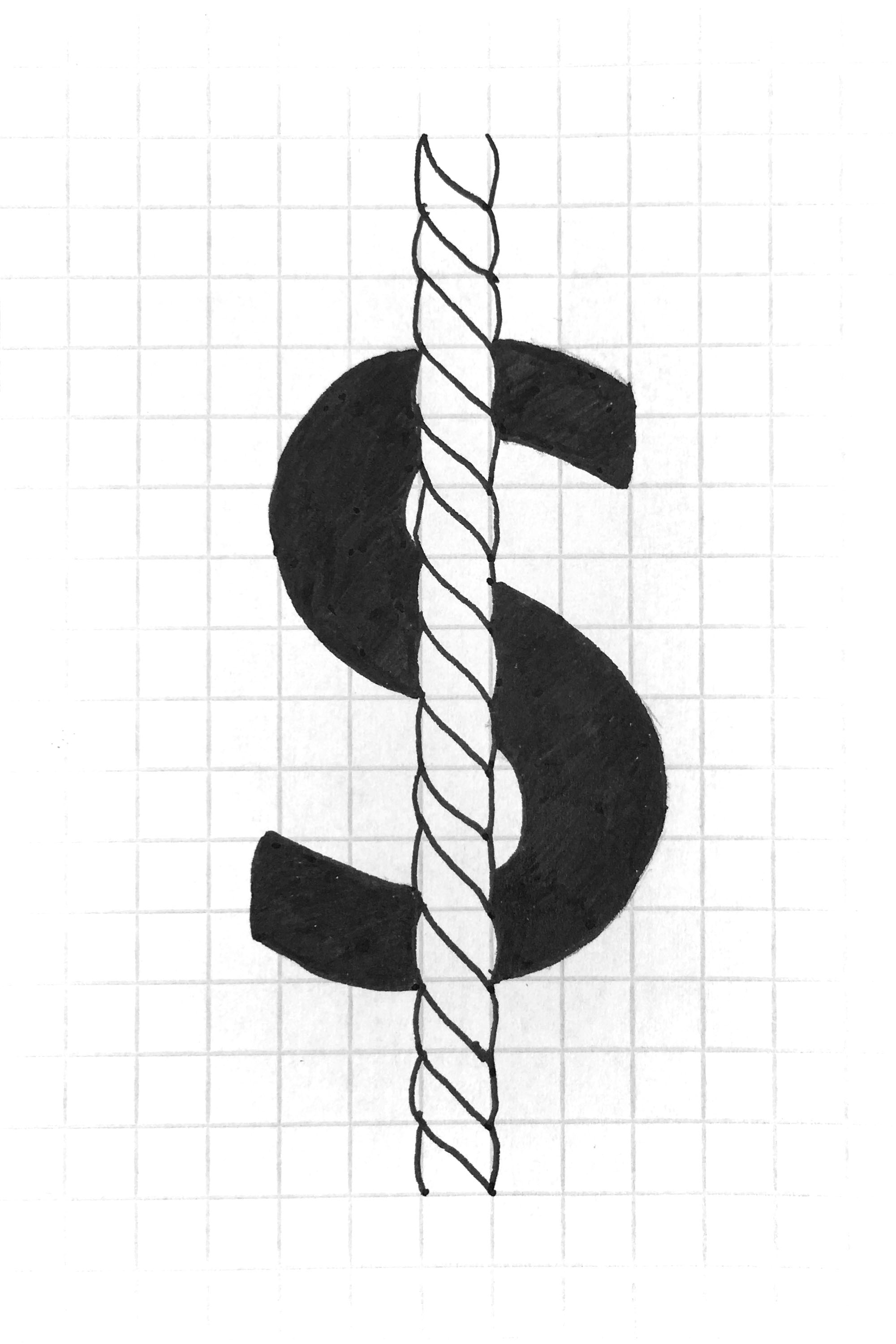

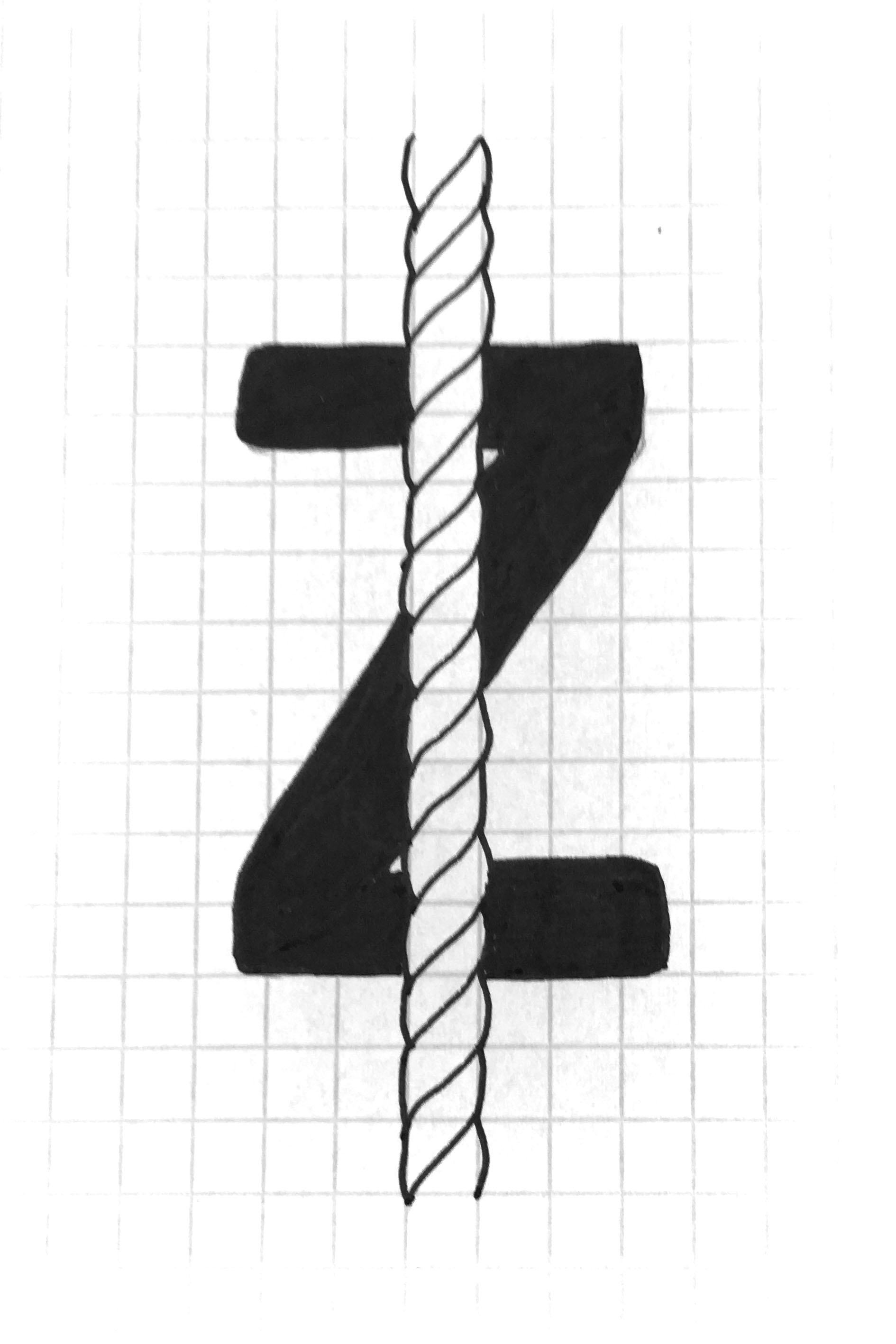

What is twist and ply?

When choosing a yarn it is important to consider the twist and ply as this affects how the yarn behaves.

Twisting yarn is the process of wrapping together (in a spiral motion) fibres to make a singles yarn and then singles to make a plied yarn. Twisting fibres together, such as when spinning, gives the fibres the strength to be woven in to cloth. Twisting these singles together to make a plied yarn adds even more strength.

The ply of a yarn is the number of singles that have been twisted together to make up a yarn. A single yarn would have a ply of one.

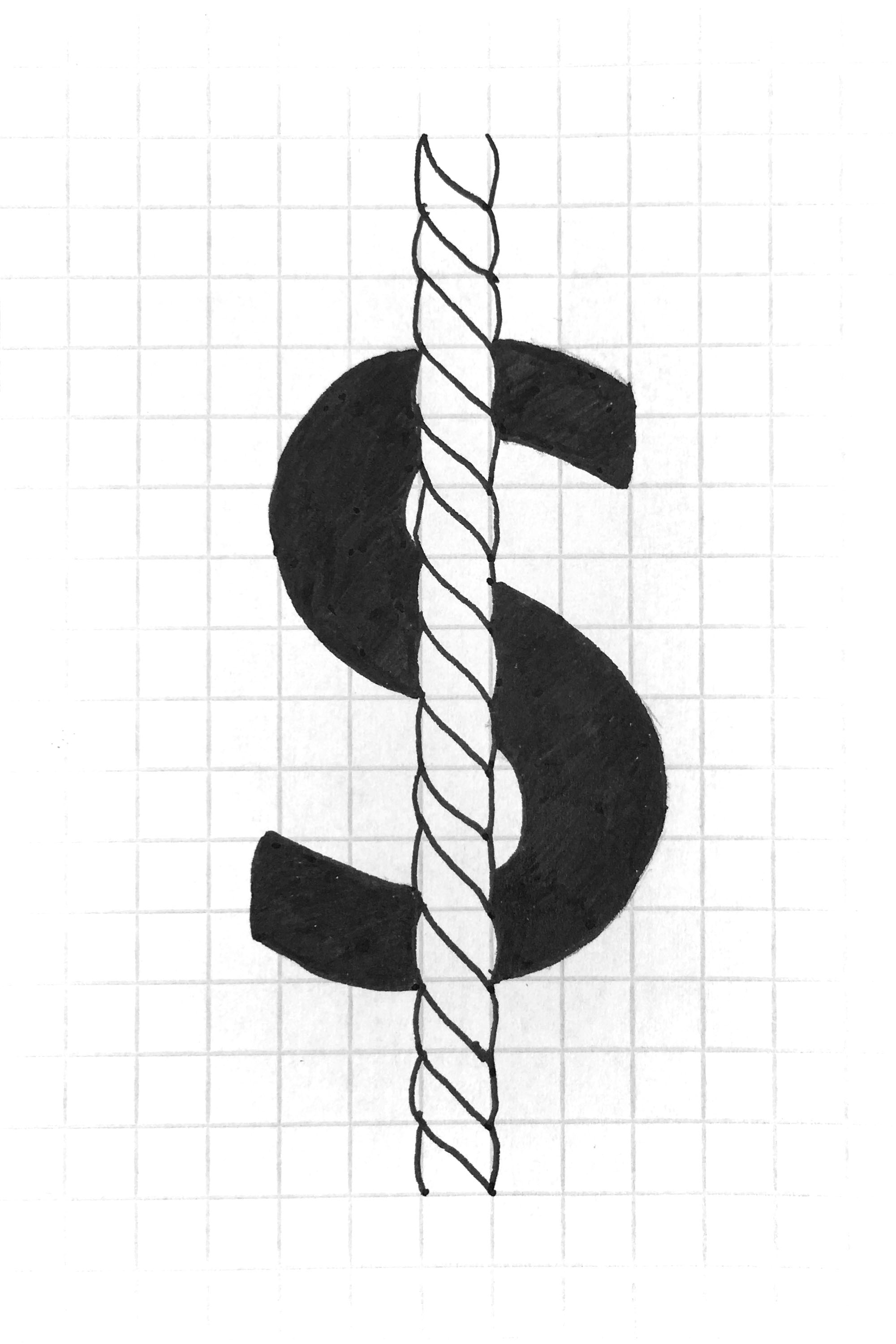

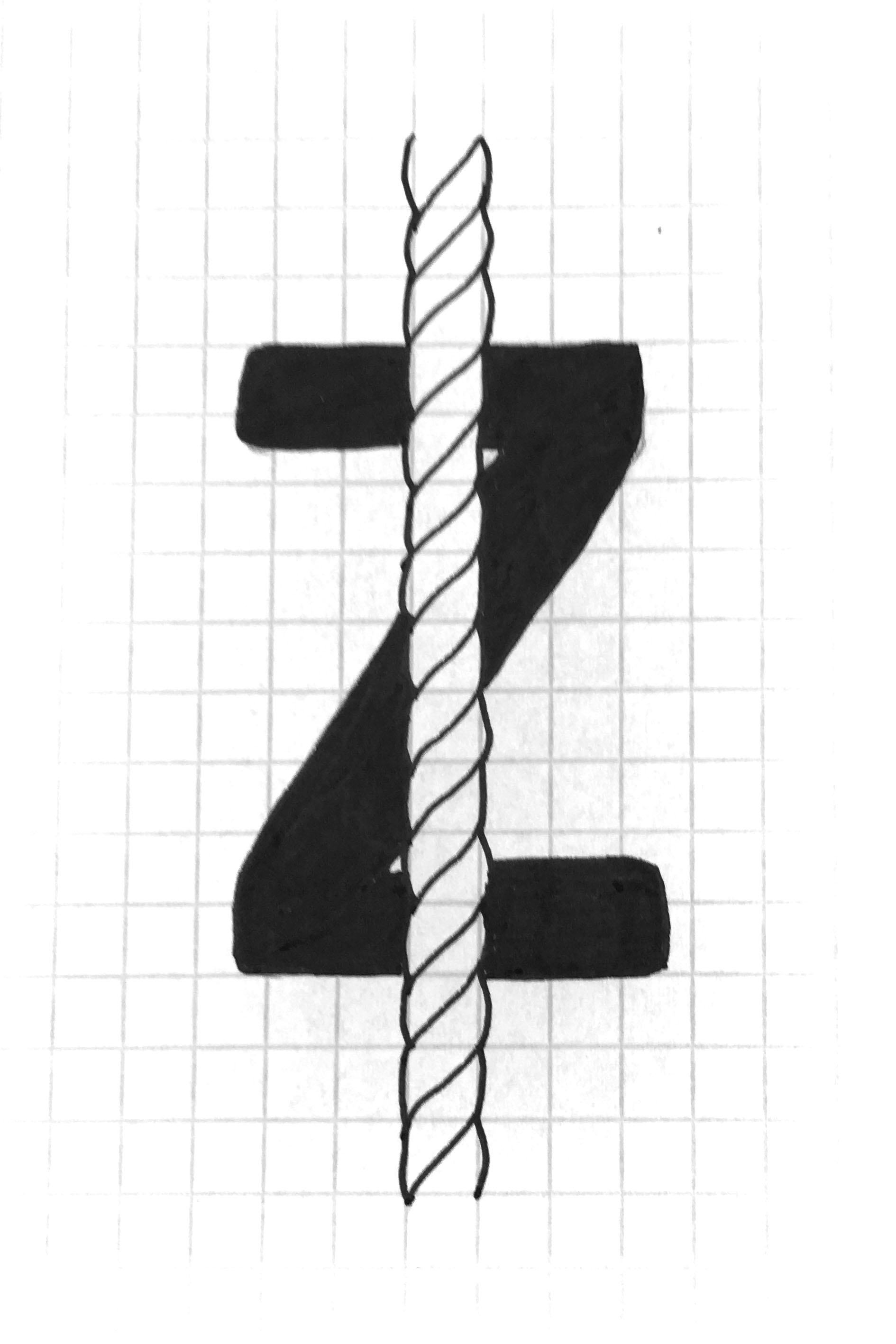

We describe the twist of a yarn as either an ‘S’ or ‘Z’ twist. To determine which way a yarn is twisted, hold the yarn vertically and visualise the diagonal in each of these letters. If the fibres appear

to be going in the same direction as the diagonal in an ‘S’ then it is an ‘S’ twist yarn. If they are going in the opposite direction then it is a ‘Z’ twist yarn.

Why is it important?

When yarn has been plied together the single strands are often ‘Z’ twist yarns which are then plied in an ‘S’ direction. If multiple ply ‘S’ twist yarns are then to be plied together, such as in a cord, they would be twisted in a ‘Z’ direction. Alternating twists in this way gives the yarn stability and strength.

If a yarn is plied together using the same direction twist as the single strands, for example the single strands were twisted in a ‘Z’ direction and the yarn was also plied in the ‘Z’ direction the resulting yarn will have a tendency to curl. This is apparent in fabrics such as voile.

The number of twists per meter is also important. This information is not always given with the yarn as standard but it will be displayed a TMI (twists per metre or TPI twists per inch). Some yarns are highly twisted and have lots of twists per meter while others are more softly twisted with less twists per meter. Shorter staple fibres will need a higher twist than longer staple fibres to give them the strength needed to be woven.

As a yarn’s TPM increases as does it’s strength until it reaches it ‘optimum twist’ (different for every yarn). Optimum twist is when the yarn is at its strongest. If twisted more than this it starts to weaken. weakening the yarn in this way is sometimes necessary to create a desired effect.

How twist and ply is applied

The twist of a singles/yarn defines the characteristics of the yarn:

| Low twist yarns |

High twist yarns |

| Softer (produce softer, lighter fabrics) |

Smoother, harder and stronger (produce finer, crisper fabrics) |

| Absorbent |

Can be water repellent |

| Less hard wearing |

More resistant to abrasion and pilling |

| Fabric more relaxed and less likely to curl |

Very high twist yarns are lively and the fabric more likely to curl |

It is very important to consider the twist of a yarn when weaving a fabric as this may help us us achieve a desired fabric. These are a few examples of some fabrics in which the twist is very important:

| Fabric |

Twist characteristics |

| Crepe |

Very highly twisted yarn |

| Voile |

Fibre spun in ‘Z’ direction with yarn also spun in ‘Z’ direction. High twist yarn which likes to curl but also creates transparency. |

| Poplin |

Yarn which has been spun in an ‘S’ twist using two singles spun in ‘Z’ twists. |

| Herringbone structured fabric |

When the yarn twist and direction of the twill structure are in opposite directions the twill will be more prominent e.g. ‘S’ twist yarn with ‘Z’ direction twill |

Sewing thread is made up of three ‘S’ twist singles then plied in a ‘Z’ direction which creates a tear resistant yarn.

Yarn Counts

by katie | Mar 23, 2018 | Blog, Weave Blog

What are yarn counts

Yarn counts can be a confusing topic but it is a useful piece of information.

The yarn count tells us the thickness and ply of the yarn. All yarn has a yarn count although this is not so obvious in some yarns such as knitting yarn which are often described in words e.g. double knit etc.

Counts are expressed as two numbers separated by a forward slash followed by the count system abbreviation e.g. 16/2 nm, 2/16wc etc. One number is the count, this tells us the length of yarn for a given weight of each individual strand of yarn. The other (usually smaller number) tells us how many strands of yarn have been plied together.

Some counts may be expressed with the ply number missing e.g. 16 nm. When a count is expressed like this it is assumed the ply is 1. Generally, the larger the number the finer the yarn.

The twist is not measured within a yarn count as each manufacturer sets this themselves. The twist of a yarn is sometimes expressed separately as twists per inch (tpi) or twists per metre (tpm).

Different measuring systems

There are many different systems used for measuring yarn. I am just going to cover the most common ones in this post.

| Count system | Yarn | Definition |

| Cotton count (cc or ne) | Cottons | 840 yards/pound |

| Worsted count (wc) | Wools | 560 yards/pound |

| Linen count (lea or nel) | Linen | 300 yards/pound |

| Numero metric count (nm or mc) | Silks | 1000 meters/kilo |

Although the different systems are commonly used for specific yarns they are often used for other types of yarn too. The numero metric count is particularly used across different yarn types.

Imperial counts (cc/wc/lea) are written ply/count

Metric counts (nm) are written count/ply

Working out the yards/pound or meters/kilo

When you know the count of a yarn this enables you to work out how many metres/yards you have per kilo/pound of that particular yarn. To work this out you multiply the number of yards/meters per pound/kilo by the yarn count. Then divide this by the ply. See the table and example below:

| Cotton count | yards per pound = (840 x count) / ply |

| Worsted count | yards per pound = (560 x count) / ply |

| Linen count | yards per pound = (300 x count) / ply |

| Numero Metric count | metres per kilo = (1000 x count) / ply |

For example:

16/2 nm

m/kg = (1000 x 16) / 2

8000 m/kg

2/12 cc

y/lb = (840 x 12) / 2

5040 y/lb

When yarn is plied there is a little bit of take up so the amounts may not work out exactly but in thinner yarns this is negligible.

Being able to do this calculation is useful because it enables you to work out how much yarn you are going to need for your project.

It is also useful to be able to convert between the two:

y/lb to m/k multiply by 2.016

m/k to y/lb multiply by 0.495

(these are rounded to three decimal places)

For example:

5040 y/lb x 2.016 = 10160.64 m/kg

To convert directly between metres and yards use the following calculation:

metres to yards – multiply by 1.09

yards to metres – multiply by 0.91

Twist and Ply

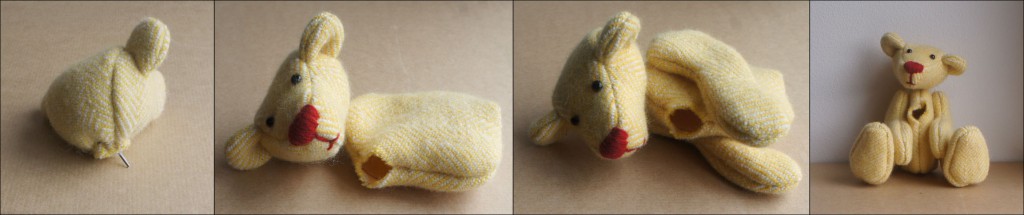

by katie | Mar 10, 2016 | Blog, How I make my hand woven teddy bears

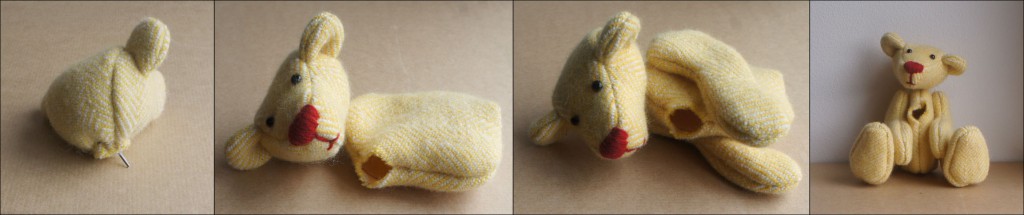

This is the final post in my blog series, I will show you how I stuff and finish my hand woven teddy bears.

The head is the first bit I stuff and use a fibre filling. I cannot use glass beads as with the rest of the bear because the head droops with the weight. Once it has shape I then work on the hand stitched nose and glass eyes. These need to be placed precisely to create a cute and appealing face.

When the head is finished it is then closed up, using a ‘drawstring’ technique. At the same time the first half of a cotter pin joint needs to be trapped inside. Cotter pin joints join all of the body parts together and allow them to move.

The body, arms and legs are then all joined, but not stuffed, using four more cotter pin joints. As the joints are put in place it is important to get them tight but not so tight that it stops movement, so some adjusting is usually needed.

The body, arms and legs are then stuffed and then hand stitched closed. I use small glass beads to stuff the body parts as it gives the teddy bear a beautiful weight and feel.

Finally, each teddy bear has a Creative Threads button of authentication sewn on.

I hope you enjoyed reading about how I make my hand woven teddy bears. If you would like to see any of the posts again they can be found here.

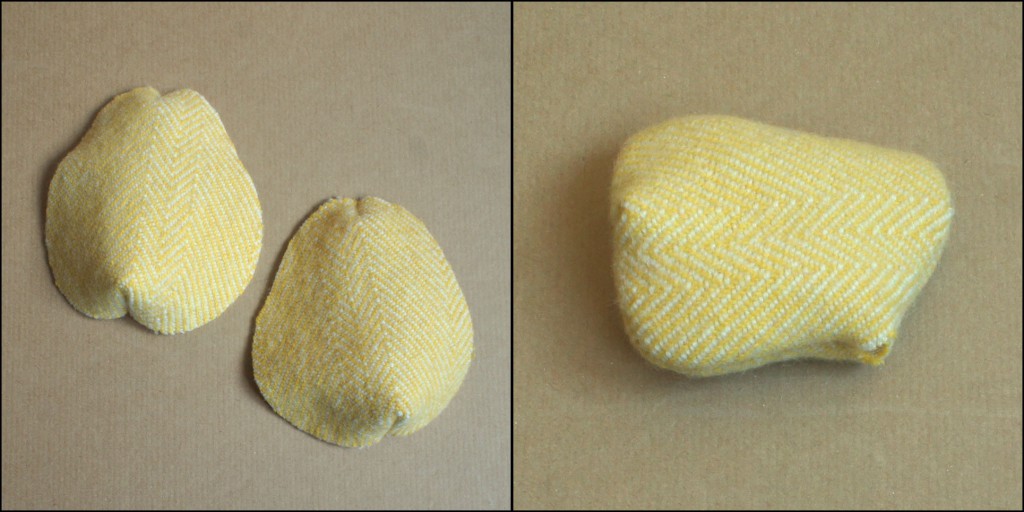

by katie | Mar 4, 2016 | Blog, How I make my hand woven teddy bears

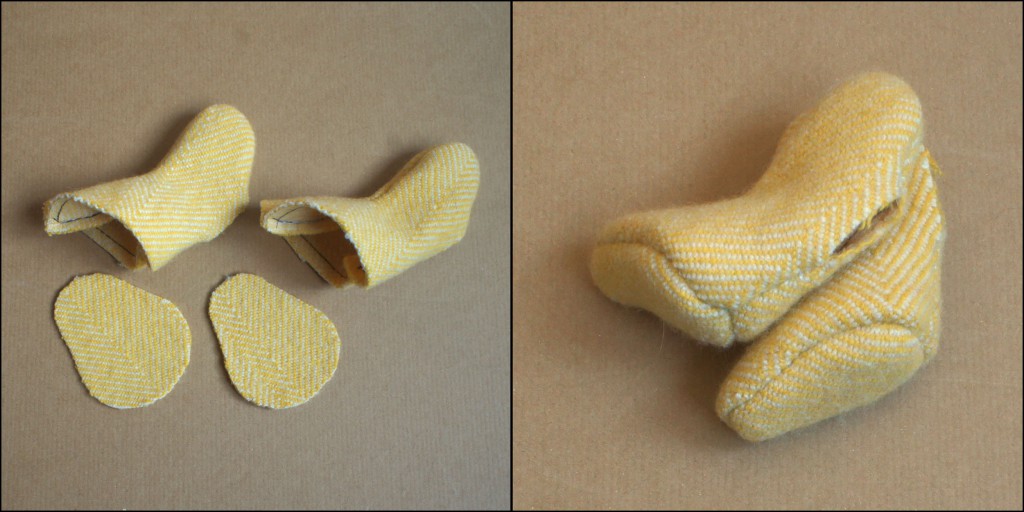

In this post you will see how the hand woven teddy bears start to take a three dimensional shape as I hand stitch the pieces together.

Due to the small size and shape of the teddy bears they all need to be sewn entirely by hand. I have tried sewing them using my sewing machine and although my it has great speed control it does not allow me to be accurate enough as I cannot see both sides at once and adjust the fitting.

The pictures show the different stages of sewing the hand woven pieces together. I normally start with the head which has the most number of stages. I start with the ears before placing them on the head and then finally inserting the central head piece.

Each piece has to be sewn accurately and lined up exactly. As you can see, the body pieces have small darts at the top and bottom. When sewn together these need to be lined up. For some of the more tricky parts, such as the head and feet, I tack (large loose stitches) them together so that they can be checked and adjusted to line up as I want them to.

When sewn together I leave an opening in each body part. This is so I can insert the cotter pin joints which join the pieces together while allowing them to move around, and of course allows me to stuff the teddy bear.

Look out for my next blog post when the teddy bear will really take shape with stuffing.

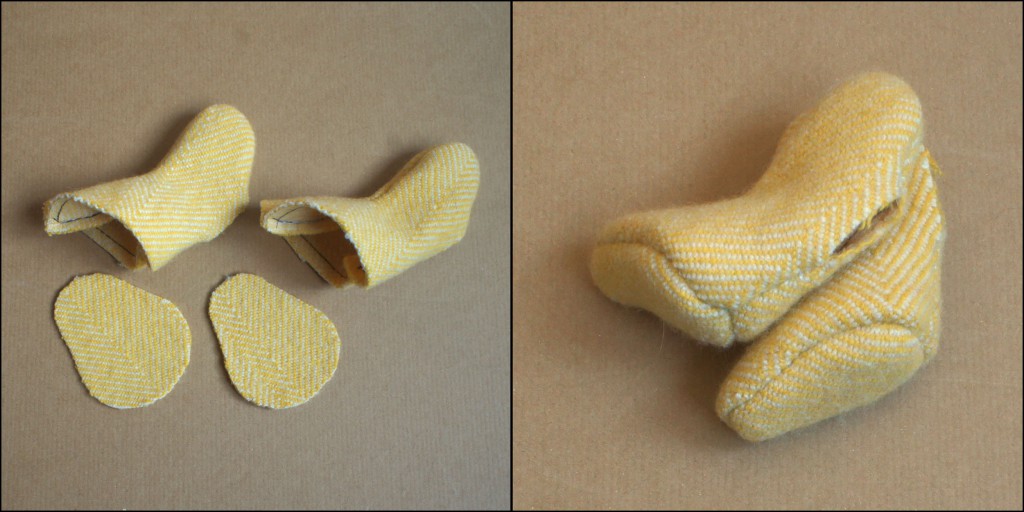

by katie | Feb 26, 2016 | Blog, How I make my hand woven teddy bears

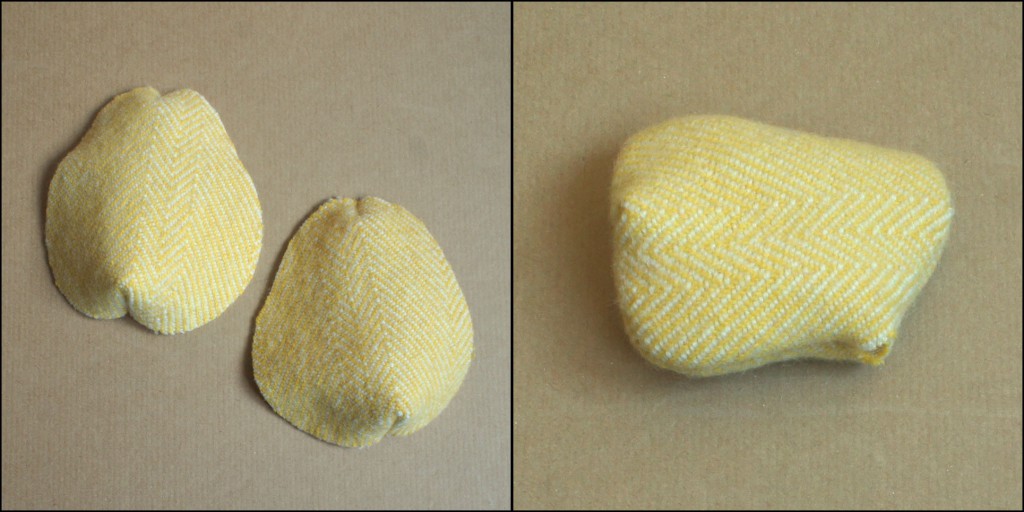

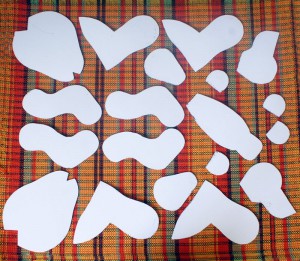

Cutting out the pieces for the teddy bears seems like a quick, simple step that doesn’t deserve it’s own post but it is a vital step that requires a lot of consideration.

Once the fabric has been woven I wash and iron it. This softens the fabric and if it is a woollen fabric then it helps to tighten the weave.

The pattern of the fabric really determines where I place the teddy bear pattern pieces. If the fabric is all one colour or the pattern is more of a texture then I would probably just place them all on the in the same direction on the fabric with the selvedges vertical. However, if there are stripes or a larg pattern then where I place the pattern pieces really makes a huge difference to the final look of the teddy bear. The things I consider are:

- The direction I want the stripes on the teddy bear, this may be horizontal, vertical or diagonal

- Whether the teddy bear is going to be symmetrical

- How I want the pattern to cross the seams of the bear

The images below show three different ways I might place the pieces on a stripy fabric. The first shows how the pieces would be placed for vertical stripes, the second horizontal and the third diagonal. All three would also be symmetrical teddy bears.

Once I have decided how I want the teddy bear to look and therefore how I am going to place the pieces they can then be cut out as shown below.

The teddy bear is then ready to be sewn together and will start to take shape.

Have a look at my next post to find out about stitching the pieces together.

by katie | Feb 19, 2016 | Blog, How I make my hand woven teddy bears

In this post I am going to tell you how I hand weave fabric for my teddy bears. Once the loom is set up (as in my previous post) I can begin to weave my fabric. This time I am using a Countermarch loom but sometimes I will use different looms which means the weaving process is slightly different.

For my countermarch loom the first this to do it set up the treadles underneath, this determines the structures I am going to weave. Each treadle needs to be tied to every shaft. The shafts contain the heddles and each of these ties will decide whether the shaft will be lifted up or pulled down, this is how the structures are created.

Treadles tied up to shafts

When a treadle is pressed with the foot and the shafts lifted or lowered it creates a triangle shaped gap in the warp called the shed. A shuttle containing the weft (horizontal threads) is passed through the shed, the fabric begins to be woven.

Shed

The treadles are pressed in a certain order depending on what I am weaving, sometimes all twelve treadles will be used, sometimes only four may be needed. As more and more weft threads are interlaced with the warp threads the fabric grows longer. I will weave a few different fabrics from the same warp. Using different patterns and weft threads means I can produce very different fabrics from the same warp.

Woven fabric with shuttle

Have a look at the next step – cutting the pieces

by katie | Feb 13, 2016 | Blog, How I make my hand woven teddy bears

In this post I will talk about setting up the loom ready for weaving which involves putting the warp on to the loom. These threads need to be put on the loom in a very particular way to enable hand weaving.

First of all one end of my warp is wound on to a rotating beam at the back of the loom. To ensure the threads are spread across the width of this beam evenly I use a raddle which is a wooden bar with nails at half inch intervals. The threads are sectioned into half inches, between each of the nails.

Warp wound on to back beam through raddle

Each individual thread is then put through a separate heddle, for my handwoven teddy bears there can be around 800 threads. Heddles are pieces of polyester thread which have an eye like a needle in the middle. Each of thread needs to be threaded in a certain order and through a particular heddle. This controls the types of patterns that will be handwoven on the loom.

Warp threads threaded through heddles

It is really important that when I weave my fabric for my teddy bears the threads are distributed evenly across the width of the fabric, and not too close together or too far apart. This is set using a reed which has a certain number of gaps per inch. A set number of threads is put through each of these gaps, usually two or three.

Warp threaded through reed

The other end of the warp is then tied on to a rotating beam at the front of the loom. The tension of each and every thread must be the same to avoid problems when weaving.

Warp tied to fron beam

I will then have my set of threads (the warp) tied from the back of the loom to the front of the loom under tension, threaded through the heddles and reed. These form all of the vertical threads in my final fabric. At this point I am ready for weaving.

Warp ready for weaving

Have a look at the next step – weaving the fabric